Your support makes these stories possible.

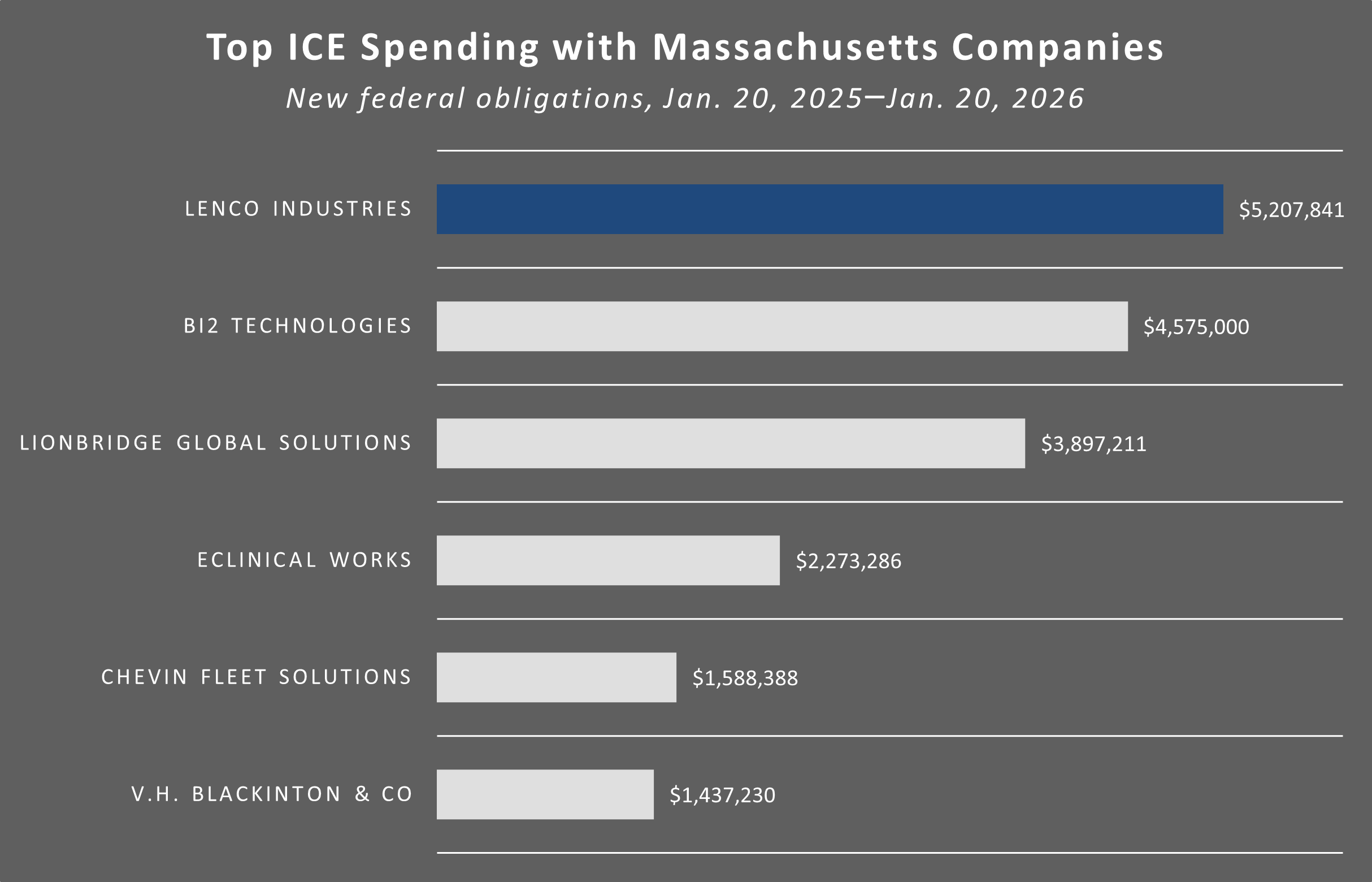

Top ICE contractor: During the first year of the second Trump administration, Pittsfield-based Lenco Industries received more new ICE spending than any other Massachusetts company.

Vehicles deployed: Lenco’s BearCat armored vehicles have been used prominently in ICE enforcement operations, protest responses, and agency recruitment.

Public support: Over the same period, Lenco received state grants aimed at expanding production capacity.

Limited response: Lenco and most Massachusetts officials contacted for this story did not respond. One exception, State Senator Paul Mark, said the company should consider suspending new sales of armored vehicles to ICE.

As outrage over U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has intensified—driven by raids and indiscriminate sweeps carried out by masked agents, violent suppression of street protests, and the killing of two Minneapolis activists—political leaders across Berkshire County and Massachusetts have called for expanded oversight, defunding, and even abolition of what they describe as a militarized and unaccountable federal agency.

“We cannot give one more penny to Trump’s ICE while its masked, poorly trained agents terrorize people all across this country,” U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren said last week. She called for “meaningful oversight over an out-of-control ICE” and suggested the agency should be “stripped down to its studs.”

Governor Maura Healey last month announced executive actions and legislation she said would constrain ICE, citing “unlawful and unconstitutional actions by ICE that are meant to intimidate and instill fear in our communities, including against United States citizens who are exercising their constitutional rights.”

Amid the increasingly sharp public denunciations from Democratic officeholders, however, one fact has gone largely unmentioned.

Since the beginning of the second Trump administration on January 20, 2025, ICE has spent more than five million dollars on armored vehicles manufactured by Pittsfield’s Lenco Industries, making Lenco the largest in-state recipient of new ICE spending, according to federal procurement data reviewed by The RGM Dispatch.

While Lenco may be the largest recipient, it is not the only one: Nineteen Massachusetts-based companies received new ICE spending obligations during the same period, either through preexisting purchase agreements or new contracts, a fact that has drawn little public attention.

Lenco, a family-run manufacturer in business for more than forty years, makes the BearCat—an acronym for “Ballistic Engineered Armored Response Counter Attack Truck”—a military-style armored personnel carrier designed to withstand high-caliber gunfire. Based on public procurement price lists, the vehicles range in price from $250,000 to more than $450,000, depending on model and features.

Over the past year, the BearCat has become a familiar presence in immigration raids by ICE and other Department of Homeland Security forces, at federal responses to anti-ICE protests, and in Trump administration hype videos and ICE recruitment pitches.

Images of Lenco BearCats used in immigration operations since early 2025. (U.S. Department of Homeland Security)

That presence became visible in western Massachusetts one morning last May, when a BearCat bearing D.H.S. license plates rolled into a downtown Great Barrington parking lot. A half-dozen ICE agents, heavily armed and moving in formation, spilled out, climbed a three-story fire escape, and arrested a man living above a local business.

The show of force—which has since become routine in operations by ICE and Customs and Border Protection nationwide—struck observers as unnecessary and brutal. The man, a Mexican national named Arturo Ernesto Lopez-Canseco, worked at a nearby restaurant. His criminal history consisted of unlawful reentry after a prior deportation and charges related to driving-under-the-influence that had been adjudicated months earlier in state court. According to federal court records, he was deported several weeks after his arrest.

For a progressive-minded town of seven thousand, the scene, which unfolded during the early months of the Trump administration’s unprecedented immigration-enforcement campaign, was shocking.

A Lenco BearCat brought heavily armed federal agents to Great Barrington in May 2025. (Edited video; footage provided by Ed Abrahams, Ben Elliott, and Avery Ripley.)

Ed Abrahams, a former Great Barrington Select Board member, was at a nearby coffee shop when the BearCat rolled to a stop within view. He stepped outside to see what was happening and began recording with his phone. Even when he lived in Washington, D.C., surrounded by multiple police agencies, he said he had never witnessed a comparable display of force. “It definitely seemed like overkill,” he told me, “just to arrest a line cook.”

Elected officials across the region condemned the raid, as they did an ICE operation in Pittsfield two months earlier, when that city’s state representative, Tricia Farley-Bouvier, made a dark historical analogy. “You can’t help but hear the echoes of the Holocaust in this,” she told WAMC Northeast Public Radio reporter Josh Landes, “when people are being rounded up and put in detention, maybe taken far away, disappeared from the community without due process.”

Her colleague Leigh Davis, who represents Great Barrington and the southern Berkshires in the legislature, said at the time that she feared “escalation” of ICE tactics.

Both said they had little power to stop federal agents. “When you are witnessing it, you want to get in and you want to fight,” Davis told constituents at a public forum a few days after the May raid. “You want to stop these people, but we cannot. They are going to come in, whether we want them to or not.”

But neither mentioned that the government vehicle that brought those agents to town—a tool of immigration-enforcement policies they have both decried—was manufactured and sold to ICE by a local company. (A Berkshire Eagle story called it “a police van” without mentioning Lenco.)

BearCats now appear regularly in action-movie-like videos posted to social media by ICE and D.H.S.—idling outside houses and apartment buildings, serving as staging platforms for raids, sometimes hauling away detainees, and often confronting protesters. Edited into fast-cut, first-person-style sequences, the videos recast immigration enforcement as a kind of tactical spectacle.

In one video filmed last September during a controversial military-style midnight raid at a Chicago apartment building, a voice can be heard yelling, “Make way for the BearCat! Clear the way for the BearCat!”

Since she became secretary of Homeland Security early last year, Kristi Noem—a skilled practitioner of political imagery—has been photographed and filmed in and around BearCats numerous times.

Secretary Kristi Noem with Lenco BearCat vehicles, in images released by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

Last fall, she also invited pro-Trump influencer Benny Johnson to accompany her on ICE operations in Chicago to help amplify her department’s show of force to his millions of followers. In one October video, Johnson cheered as BearCats ferried heavily armed agents—whom he called Noem’s “skull-crackers”—to confront protesters he labeled “left-wing terrorists” outside the agency’s Broadview Detention Center.

The operation that day prompted multiple lawsuits. The following month, a federal judge said that ICE’s violent assaults on protesters “shocks the conscience” and were “untethered” from any actual threat.

(An ICE spokesperson did not respond to e-mailed questions about the agency’s use of armored vehicles.)

A clip from the October 5, 2025 episode of The Benny Show. (Text annotations added.)

Back home, Lenco is widely regarded as a local success story. The company employs roughly one hundred fifty people, has expanded over the past decade into 170,000 square feet of factory space, and frequently partners with workforce-training programs to provide career pathways for young people. In 2022, it was named Employer of the Year by the MassHire Berkshire Workforce Board.

It also participates in civic life, if sometimes awkwardly: as BearCats rolled alongside colorful floats and marching bands in Pittsfield’s Fourth of July parade last year, children sat in their rooftop gun turrets, waving and blowing bubbles.

Lenco showcased several BearCat models during Pittsfield's Fourth of July parade in 2025. (Pittsfield Community Television)

Lenco says it has sold more than seven thousand armored vehicles to about twelve hundred state and federal agencies and police departments, with customers in all fifty states and more than forty countries. In the United States, many police departments acquire BearCats at little or no cost, using D.H.S. counterterrorism grants or other federal programs that Lenco helps police departments navigate.

Those sales have made the company a focal point in the long-running debate over the militarization of law enforcement—a characterization Lenco rejects. In 2016, the company’s owner and longtime chief executive, Len Light, who bought the business from his parents in 1992, called it “the falsely perceived militarization of police,” adding that “the shared mission objectives between military and S.W.A.T. cannot be ignored.”

Lenco argues that the nature of modern threats makes vehicles like the BearCat a practical necessity, protecting officers and saving lives; its website and social-media feeds feature a steady stream of testimonials from police officers praising the vehicles’ protection and utility.

Civil-liberties advocates counter that the spread of military-style equipment, including BearCats, alters the posture of policing itself—shifting officers from peacekeepers to warriors and increasing the risk of escalation, use of excessive force, and the erosion of public trust.

Radley Balko, a former Washington Post reporter and the author of Rise of the Warrior Cop: The Militarization of America’s Police Forces, told me that the prominence of BearCats in ICE operations appears driven less by danger than by the desire to project a newly militarized aesthetic. “It seems like they have all of this fancy gear for content generation—for the videos they post to social media—because it looks big and intimidating,” he said.

Balko said he is not categorically opposed to police agencies having bulletproof vehicles and acknowledged that some situations are genuinely dangerous for officers. But he does not see the need for them in most ICE activities. On the ground, he said, in cities like Minneapolis, Chicago, and Los Angeles, immigration agents often rely on “very plain-looking, civilian-looking cars” when making arrests.

The contrast, he said, is revealing. “I think it shows that they don’t actually fear the people they’re going after,” Balko told me. “As much as the administration claims that these are violent criminals and predators—well, then why aren’t you using the bulletproof vehicles to go after them?”

Instead, Balko said, BearCats used by ICE and other D.H.S. divisions tend to appear in places where they send a message. “They’re using them at protests, in situations where they’re trying to intimidate people and have a big show of force.”

In an October social-media post, Noem declared, “We’re not taking this anymore,” as footage showed heavily armed federal agents riding BearCats and violently arresting protesters. (ICE/Instagram)

Balko argued that what is unfolding with ICE and other federal law-enforcement agencies has eclipsed the older debate over police militarization. “I think we’re beyond that discussion at this point,” he said.

He pointed to D.H.S. recruitment messaging that, he said, increasingly relies on “openly white supremacist rhetoric and Nazi iconography,” and to agency guidance that treats anyone who films or questions agents—conduct protected by the Constitution—as a “domestic terrorist.” Immigrants, he said, are portrayed “as something less than human,” while officers are repeatedly assured that no matter how abusive their conduct becomes, they will not be held accountable.

“What we’re looking at now,” Balko said, “are paramilitary forces basically carrying out the will of the president.”

A Lenco BearCat on display at a D.H.S. recruiting booth at a Turning Point USA conference in December. (Laura Jedeed; Instagram/D.H.S)

Beginning last fall, ICE expanded its armored-vehicle purchases after Congress appropriated one hundred and seventy billion dollars for the Department of Homeland Security last summer—a package that included an unprecedented, four-year, seventy-five-billion-dollar boost for ICE, on top of its previous annual budget of roughly ten billion dollars. (Congress is reconsidering that spending amid ongoing government-shutdown negotiations.)

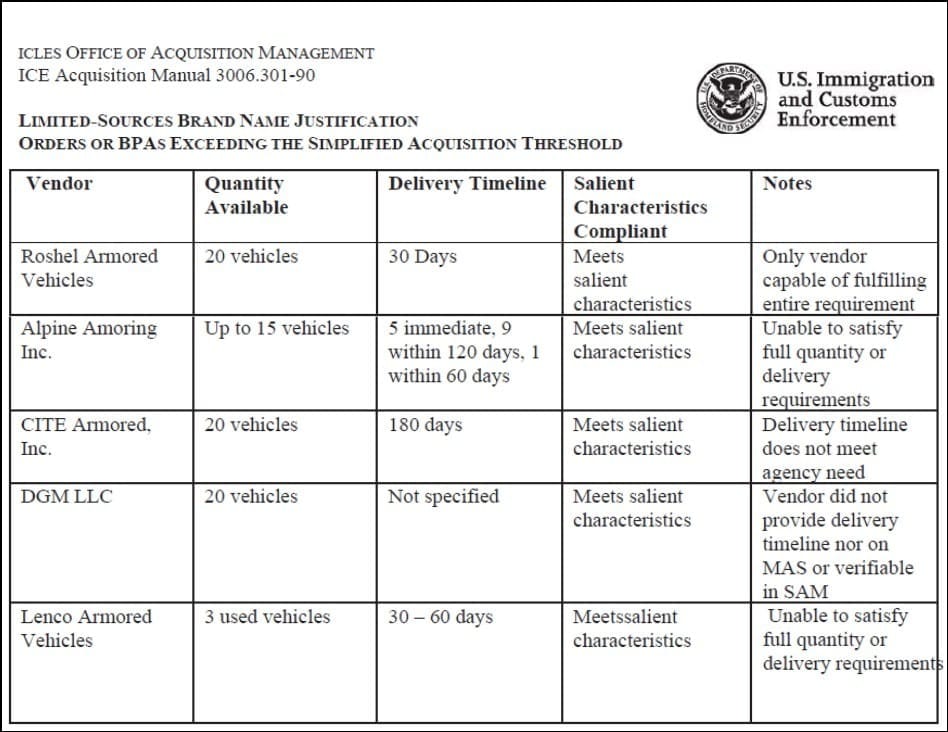

As part of that expansion, ICE disclosed plans in September to make an $8.3 million sole-source purchase of BearCats. The effort stalled, however, when Lenco could not meet the required timeline, according to federal procurement records. An ICE procurement-justification document noted that the company could supply only three used vehicles by the end of 2025—far short of the agency’s stated needs.

Instead, ICE turned to the Canadian manufacturer Roshel, rushing twenty of its BearCat-like armored vehicles into the field at a cost of $7.2 million. (Some have already been spotted in Minneapolis.) The White House and D.H.S. later showcased the new Roshel vehicles in an ICE recruitment video set to the aggressive, pumped-up strains of the popular TikTok hype song “Hooligang.”

An ICE recruitment video posted to social media by the White House and D.H.S. in December featured armored vehicles made by Roshel. (Instagram/D.H.S.)

Even so, in November the agency placed a new $4.8 million order for BearCats under an existing purchase agreement, accounting for the bulk of Lenco’s business with ICE last year. Details in a federal procurement database indicate that the vehicles are scheduled for delivery by the end of May—a chronology confirmed by an ICE spokesperson.

Over the last year, Lenco has also received $345,600 in state grants to help expand its production capacity and retrain workers: two hundred thousand dollars from the Massachusetts Technology Collaborative’s advanced-manufacturing program—designed to help companies scale up to meet customer demand—and the remainder from a state workforce-training program.

In MassTech grant-application materials obtained by The RGM Dispatch through public-records requests, Lenco described itself primarily as a defense contractor. In the application narrative and accompanying video, which appear to have been submitted in April 2024, the company listed customers including military branches and the Department of Energy, as well as “the F.B.I., C.I.A., A.T.F., U.S. Marshals, and a host of other federal agencies,” but did not specifically mention the Department of Homeland Security or ICE. “We have an exciting future,” Jim Massery, the company’s U.S. sales manager, said in the video, “but we do need to expand.”

The MassTech grant, announced in September 2024, was awarded after Lenco sought funding for new robotic-welding equipment. Last May, the company asked MassTech to redirect the grant toward different machinery—a request that was quickly approved, according to e-mails reviewed by The RGM Dispatch. State payment records show the funds were disbursed in December.

At a ribbon cutting in mid-December to unveil a new two-million-dollar laser-cutting machine, funded in part by the MassTech grant, Light said, “We’re busier than we’ve ever been, and with the changes we’re making in production with this new equipment, we’ll be able to meet the increasing demand.”

The machine is part of broader planned investment that, the company says, will streamline operations and increase production capacity by as much as thirty per cent.

Images from a MassTech grant-application video show Lenco's 170,000-square-foot facility. (MassTech)

Lenco’s sales to ICE are not new—and represent only a portion of its sizable federal business. Federal records show that since 2017 the agency has paid more than sixteen million dollars for BearCat vehicles. Over the same period, Lenco’s federal revenue totaled roughly $142 million across all government agencies, largely from the Departments of Defense and State.

(Lenny Light, Lenco’s executive vice president, did not respond to requests for comment or e-mailed questions about the company’s sales to ICE.)

Even as Massachusetts officials have escalated their attacks on ICE and the Trump administration’s increasingly violent mass-deportation campaign, the role of Massachusetts companies in supplying the agency has gone largely unexamined.

In early January, Maura Healey, who last month launched her campaign for a second term, called on two private air-transport companies—neither based in Massachusetts—to stop providing deportation flights out of an Air Force base near Boston that is located a few miles from an ICE detention center.

In a sharply worded letter, Healey described the agency’s tactics as “brutal,” “intentionally cruel,” and “anti-American,” focusing on denial of due-process rights. She urged the companies—Eastern Air Express, based in Kansas City, and Miami’s GlobalX Airlines—to cease supplying “services or equipment” to ICE “in any capacity.”

Asked in multiple e-mails whether the same standard should apply to Massachusetts-based companies like Lenco, the governor’s spokesperson, Karissa Hand, did not respond.

One elected official suggested that it should. Paul Mark, a state senator whose western Massachusetts district includes Pittsfield, said Lenco should consider suspending sales of armored vehicles to ICE, framing the issue as one of corporate responsibility.

“If they’re seeing something, philosophically, that they and the community don’t like,” he told me last month, “maybe they could pause some of those contracts—or at least not take new ones for a while.” He added that he would be more inclined to advocate on the company’s behalf for future state grants if it did so.

Many others declined to engage. Peter Marchetti, the mayor of Pittsfield, declined multiple interview requests and did not answer e-mailed questions about Lenco. In a statement, his office said it would not comment “on any specific business and any contracts that they may or may not have.”

Requests for comment sent to state Rep. Leigh Davis; Carolyn Kirk, the chief executive of the Massachusetts Technology Collaborative; the governor’s Executive Office of Labor and Workforce Development; U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren; U.S. Rep. Richard Neal, and Ben Sosne, who heads the Berkshire Innovation Center—which partnered with Lenco to secure the MassTech grant—went unanswered.

Jeromie Whalen, a South Hadley teacher challenging Neal in this year’s Democratic primary, called ICE “a disgrace to the hard-working local law enforcement officers who already protect our communities,” and said the agency should be abolished. He said state grants to Lenco should continue to support its manufacturing of fire, rescue, and emergency-medical vehicles, but did not say how such funding would be separated or whether the company should suspend sales to ICE.

(Disclosure: I was a candidate in the 2012 Democratic congressional primary won by Neal.)

Rep. Seth Moulton, who is challenging U.S. Senator Ed Markey this year, did not respond; Markey replied with a statement condemning ICE but did not address questions about Lenco.

One lawmaker said she is still weighing the issue. Tricia Farley-Bouvier, the state representative who last spring likened ICE raids in Pittsfield to patterns of state violence associated with the Holocaust, told me last month that she needs more time to gather information. She said she had not been aware, until recently, of how Lenco vehicles are used by ICE, and wants to “carefully look at it and ask a lot of questions” before taking a position.

Still, she said, attention must be paid. “In this moment in our history, ICE needs to be looked at very differently,” she said. “We should be talking about this.”

∎ ∎ ∎

Data & method: USAspending.gov transaction-level data; new ICE contract obligations recorded January 20, 2025–January 20, 2026, not total contract values.

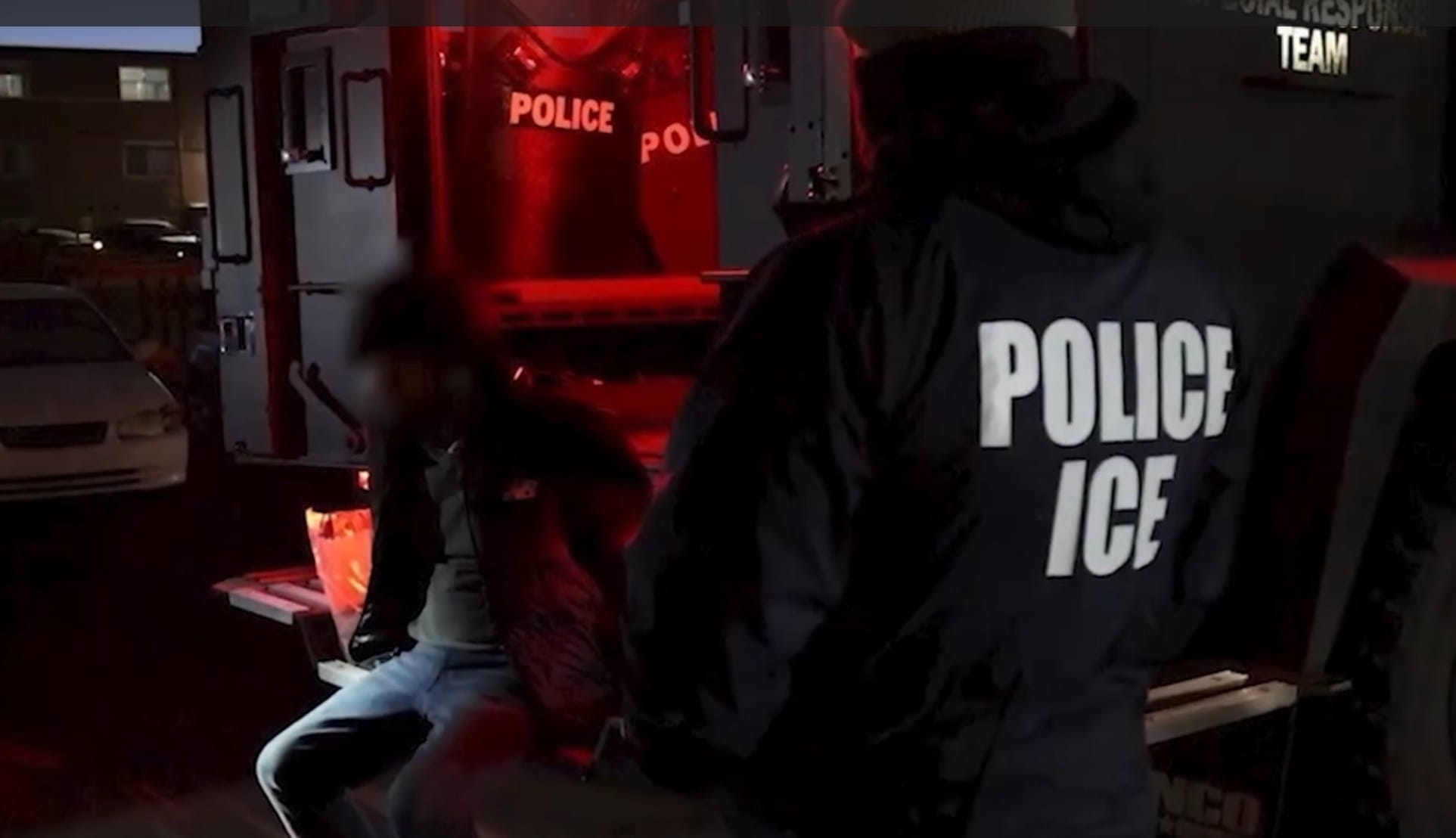

Featured photo: An ICE officer watches protestors as a Lenco BearCat vehicle drives to the scene in the Brighton Park neighborhood of Chicago, on Saturday, October 4, 2025, after protesters learned that U.S. Border Patrol shot a woman on Chicago’s Southwest Side. (Anthony Vazquez/Chicago Sun-Times via A.P.)