Your support makes these stories possible.

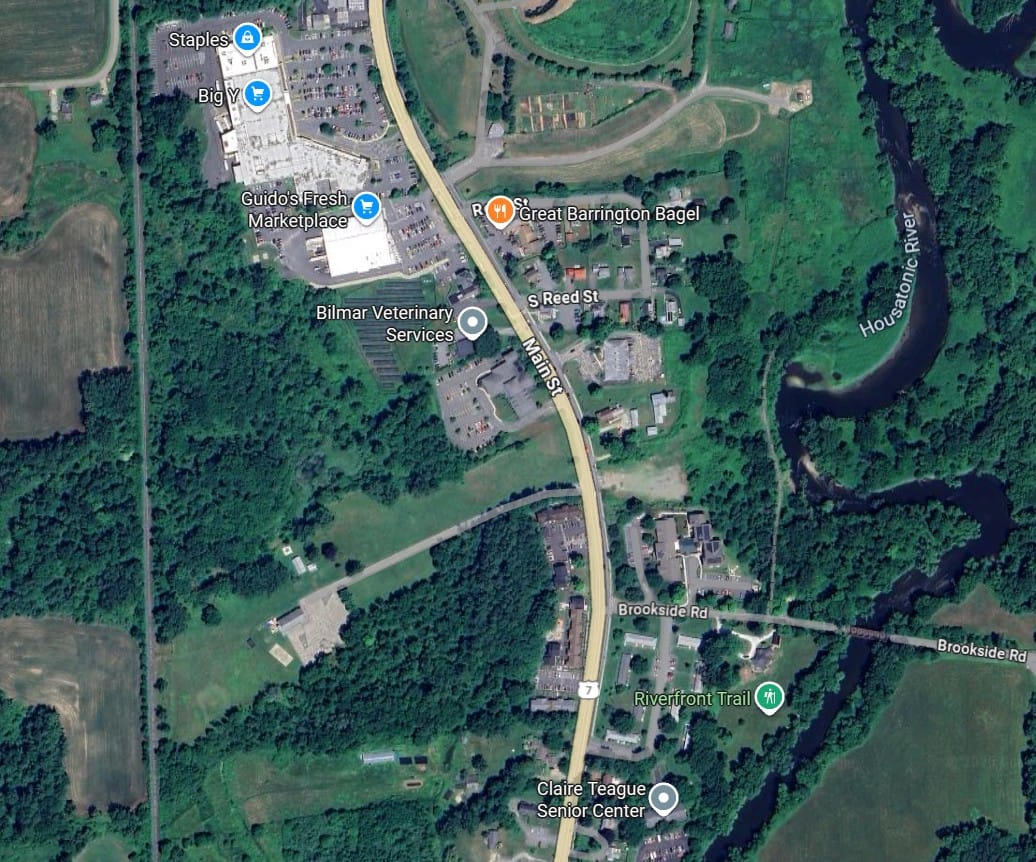

Five years ago, after her Louisiana home was destroyed in a hurricane, Nora Burch, a retired kindergarten teacher, moved to Brookside Manor, the public-housing apartments on South Main Street in Great Barrington. She’s thrilled to be there.

“My daughter lives up here, and I kept visiting. I just love the area,” she told me last week. Her late husband was a veteran, a fact that helped her qualify for affordable senior housing at Brookside.

At seventy-eight, she’s active: volunteering a few days a week at the town-run Claire Teague Senior Center, tending herbs at the Berkshire Botanical Garden, and occasionally heading out to hit golf balls with her daughter.

One thing she won’t do? Walk across South Main Street to reach the grocery stores or nearby shops—even at the crosswalk at South Reed Street, a short walk from her apartment. “Oh, no—when I first moved up here, my daughter forbid me. She said, ‘Do not cross that street, Mom. People are not looking,’” Burch said. “We’ve had that understanding ever since I moved up here, and I listened.”

Some of her Brookside neighbors are more adventurous—but still afraid. “When the weather is nice, they like to get out and walk and pick up a few groceries,” she said, mentioning the nearby Big Y. “They wear a bright vest, but they’re still leery about walking. They’re actually kind of scared to go.”

And for good reason. The danger Burch describes is not hypothetical: fatal pedestrian crashes at the South Reed crosswalk date back nearly two decades.

In May 2006, Nellie Styczynski, a seventy-nine-year-old Brookside Manor resident, was returning home after her daily walk to the Big Y when she was struck and killed by a southbound vehicle as she stepped into the crosswalk. At the time, the crossing was configured diagonally across South Main Street. And, crucially, there were no pedestrian warning lights.

In the aftermath, private citizens—not the town—raised twenty-five thousand dollars to pay for new warning lights at the South Reed crossing and at several downtown locations. The crosswalk was also reconfigured to its current perpendicular alignment. And at the Select Board’s urging, the town’s public-works department repainted crosswalks across town and police promised closer enforcement.

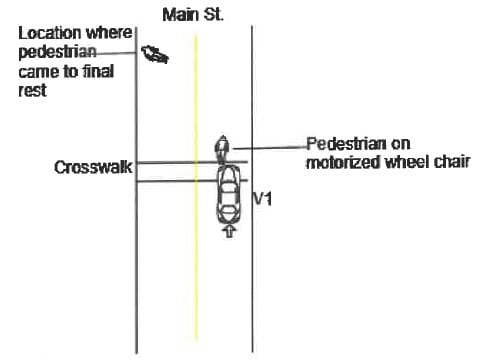

It was not enough. Nine years later, in September 2015, Stuart Dupuis, a sixty-two-year-old Air Force veteran who also lived at Brookside, was struck by a southbound driver and killed while crossing South Main Street in his motorized mobility scooter.

According to the police crash-reconstruction report I reviewed last week, it’s unclear whether Dupuis was inside the crosswalk or just beyond the lines when he was hit. In either case, witnesses told police they didn’t see the crosswalk’s warning lights flashing at the time of the collision.

For more than a decade after that second fatality, the crossing and surrounding roadway remained unchanged. Then, on January 13, Gary Fretwell, a seventy-year-old Brookside resident who had lived in Great Barrington for a quarter-century, was struck by a southbound pickup truck as he traversed the same crosswalk. Flown by LifeFlight helicopter to Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, he spent ten days in a coma before succumbing to his injuries. He was the third Brookside Manor resident to die at the South Reed crossing.

The town’s interim police chief, Adam Carlotto, confirmed that the pedestrian warning lights at the crosswalk—activated by a motion sensor—were not functioning at the time Fretwell was hit.

Across three fatal crashes spanning twenty years, the same crosswalk—the only one that serves one hundred and forty nearby apartments reserved for income-qualified seniors and families—has remained largely unchanged. Despite a 2018 town survey that ranked South Main Street as a top priority for improved streets, sidewalks, and crosswalks, little has been done.

The persistence of danger has not gone unnoticed. As previously reported, the need for safety improvements along more than a mile of South Main has long been known to current and former town officials, as well as residents and workers in the area who have repeatedly raised concerns about pedestrian safety.

At least one of those warnings came just three months before Fretwell was killed. According to e-mails sent in October to Great Barrington elected and municipal officials, and shared with The RGM Dispatch on condition of anonymity, a Brookside resident alerted town officials that the pedestrian crossing system at the South Reed crosswalk was not working.

“Each time I cross the street,” the resident wrote on October 11, “I am at significant risk due to the disabled lights at the crosswalk.” The e-mail noted “two near-accidents with inattentive motorists in recent weeks,” despite the resident's exercising “great caution.”

The resident reminded the eleven recipients, including four Select Board members, among them Chair Stephen Bannon, as well as the then-interim town manager, Chris Rembold, that “many residents from Brookside, Windrush, and Bostwick properties”—the three affordable-housing developments on either side of Route 7—“also rely on this route.” The e-mail also highlighted deteriorating sidewalks that were difficult to navigate safely by people using mobility devices, such as walkers.

The e-mail closed with a request for “immediate attention to these safety issues to help protect all pedestrians who use this route.”

For nearly six weeks, the resident said, there was no response. Then, on November 19, Select Board member Philip Orenstein forwarded the message to Great Barrington’s new town manager, Liz Hartsgrove, copying Bannon and others. (Hartsgrove had begun serving as town manager earlier that month.)

That evening, Hartsgrove replied to the resident, acknowledging the complaint and writing that she was “seeking information from the appropriate departments.” The resident told me that was the last communication about the matter.

The resident later e-mailed the town’s public-works supervisor, Joe Aberdale, after being told that her original message had been forwarded to him by Bannon, but received no reply.

Carlotto told me that the crosswalk lights were repaired at some point in late December. By January 13, they were no longer functioning. Two days after Fretwell was struck, workers were seen repairing them again.

When I reached out last week to Orenstein, who also serves as chair of the Great Barrington Housing Authority, which oversees Brookside Manor, he declined to comment and referred questions to Hartsgrove and Bannon. Aberdale also referred questions to Hartsgrove.

Bannon did not respond to e-mailed questions, including about how the town prioritizes long-discussed South Main Street improvements. In an e-mail last week, he said he was away and unable to respond, and later said he could speak only briefly by phone, but no interview took place.

In an e-mail response, Hartsgrove declined to answer questions about what steps were taken, and by whom, after the October 11 e-mail; when the crossing lights were inspected or repaired; or whether there are current plans for safety improvements. She said she would issue a statement at the next Select Board meeting.

∎ ∎ ∎

Beyond questions of maintenance and response, traffic-safety experts say the area around the South Reed crossing suffers from various unaddressed issues. Michael Knodler, a traffic-safety engineer and director of the UMass Transportation Center, said the area exemplifies a common—and dangerous—mismatch: a high-speed state highway that abruptly connects into a residential zone with a population that includes many older pedestrians.

In environments like this, Knodler said, speed is the decisive factor. “If a driver is going forty miles an hour, there’s about an eighty percent chance the pedestrian will be seriously injured or killed,” Knodler told me recently. “At twenty miles an hour, that flips—there’s about an eighty percent chance they won’t be.”

At South Reed, the crossing relies on passive motion detection that activates flashing lights automatically—without a push button, audible signal, or clear visual confirmation to pedestrians that the system has engaged.

Knodler said that design can become especially dangerous at night; the 2015 and 2026 fatal accidents both occurred about thirty minutes after sunset. “The challenge with just passive detection is that when it doesn’t work, it can be catastrophic,” he said. “The pedestrian might assume it’s working. The driver, if they’re familiar with that location, might assume it’s working. And if it’s dark, neither one of them might be doing anything wrong. And then you’ve got a system that’s failed them.”

Pedestrian safety improves when protections are layered—what Knodler called “stacking”—so drivers receive multiple, unmistakable signals that they are entering a different environment. That’s particularly important in an environment like South Main, where northbound traffic comes directly from a higher-speed state highway and southbound drivers may accelerate to highway speeds prematurely.

Safety measures, Knodler said, can include raised crosswalks that physically slow vehicles; median dividers that signal a change in roadway context; advance pavement markings and yield lines set well back from the crossing to prevent “multi-threat” crashes; pedestrian signals with push buttons and audible or visual confirmation; and modern crosswalk-lighting systems that illuminate pedestrians at night.

Newer crosswalk systems may include illuminating lights that improve pedestrian safety at night. (TAPCO)

At Reed Street, most of those elements are absent. The crosswalk paint has faded; there are no advance yield markings on the pavement; the existing beacon flashes slowly; and the system activation does not provide any feedback telling pedestrians whether it is working.

Newer systems use Rectangular Rapid Flashing Beacons, or R.R.F.B.s, like those installed at several downtown Great Barrington crossings and at a traffic circle built in 2022. The rapidly flashing lights are “extremely effective,” Knodler said. Federal Highway Administration data indicate they can reduce pedestrian-involved crashes by nearly fifty percent and increase driver yield rates to as high as ninety-eight percent, depending on speed limits and other factors.

Left: The pedestrian beacon at South Reed Street, first installed in 2007, flashes slowly when activated. Right: Rapid-flashing beacons installed at several downtown Great Barrington crossings, which federal data indicate can reduce pedestrian crashes by nearly fifty percent. (Bill Shein/RGM Dispatch)

Knodler said replacing the existing beacon with a modern R.R.F.B. crossing system would likely cost less than twenty-five thousand dollars—roughly the same amount that residents raised after the first fatal crash nearly two decades ago.

But he cautioned that often, no single device or traffic feature is sufficient on its own. He pointed to downtown Great Barrington’s multi-lane intersections where a stopped vehicle can obscure a pedestrian from a vehicle approaching in an adjacent lane. In those cases, he said, additional measures, including prominent pavement markings well before the intersection—which are not present downtown—can help.

(In 2022, while serving on the Select Board, State Rep. Leigh Davis argued downtown’s four-lane configuration posed a danger to pedestrians and pushed unsuccessfully for reducing the number of travel lanes. Her proposal failed on a four-to-one vote, with other board members, including Bannon, arguing that new flashing beacons and a center “refuge” island were sufficient.)

A walk from Windrush Commons to nearby shops. (Bill Shein/RGM Dispatch)

Despite the availability of proven fixes, little has been done. The South Main Street corridor—more than a mile long—needs rebuilt roadways, continuous sidewalks, safer crossings, and traffic-calming measures. There is no sidewalk that directly links Windrush Commons, which opened in 2023, with the rest of town, leaving those residents walking on the Route 7 shoulder. Several crosswalks farther north have no warning lights at all. And at South Reed, the crosswalk appears little changed since 2007.

But a full redevelopment project, which was first proposed in late 2017 at an estimated cost of seven million dollars, has languished. In the meantime, it remains unclear why even modest-but-impactful safety improvements at South Reed, in particular, have not been made.

Despite three fatalities, the contrast with attention paid to other parts of Great Barrington is notable. Last year, when residents of the East Street neighborhood raised longstanding concerns about speeding and pedestrian safety along a popular downtown bypass route, the Select Board responded within months—placing the issue on its agenda, hearing from residents, consulting police, and implementing changes that include new stop signs and crosswalks.

For South Main Street residents and business owners, the consequence of delay is visible every day. Bob Climo, whose Great Barrington Bagel Company sits a few hundred feet north of the South Reed crosswalk, told me he regularly sees people—including children—walking in the roadway. From his storefront windows, he can see the crosswalk and pedestrian traffic. “There needs to be a traffic light there,” he said. “It’s just not working like this.”

Christina Koldys, whose mother, Nellie Styczynski, was killed in the crosswalk in 2006, told me that every year on the anniversary of her death, she posts a copy of a Berkshire Eagle profile written at the time. The two paragraphs that describe the accident are blacked out with heavy marker.

She said she posts the story so that “our police force, our Select Board, our community, and each individual remembers and is aware of the danger when we cross a street in our city.”

Koldys recalled an increased police presence near crosswalks for a few summers after her mother’s death, but said it soon faded. She’s frustrated that little has changed. “The lyrics to a song play in my head: ‘When will they ever learn, when will they ever learn,’” she said.

Mickey Maki, whose home is just south of Windrush Commons, said her mother lives across Route 7 at the Bostwick Gardens senior apartments. “She walks back and forth across the street, so it’s definitely a serious concern for us,” Maki told me last week.

(Hearthway, the nonprofit housing organization that manages both Windrush Commons and Bostwick Gardens, did not respond to e-mailed questions about pedestrian safety near its properties.)

Maki said her mother can sometimes have difficulty walking, so the extra distance north to the South Reed crosswalk and then back south past Windrush—along a long stretch of Route 7 with no sidewalk—is too much.

Instead, she crosses at Brookside Road, where there is no crosswalk. “She’s only willing to cross when there’s no traffic at all,” Maki said. “Once the morning traffic starts, she won’t cross. I’ll go pick her up. We don’t risk it.”

∎ ∎ ∎

On January 24, as news spread of Fretwell’s death, friends posted remembrances and shared their heartbreak on social media. He worked for many years at local restaurants and was a beloved dog walker and pet sitter.

Nelson Fernandez, who met Fretwell after moving to the area in 2020, told me they often got together for breakfast at a downtown coffee shop. Those meals were “a constant in my life,” he said, describing Fretwell as “a deeply loyal friend with a wicked sense of humor and a generous heart.”

Nan Wile, another friend—and someone who previously warned Select Board members about traffic speed and pedestrian safety on South Main—told me that Fretwell moved last year from downtown Great Barrington to a Brookside apartment.

“He was so pleased to be walking distance to Guido’s, Big Y, and the Housatonic River Walk,” she said, describing two grocery stores and a popular walking trail. When she saw him recently, he told her he was logging about three miles a day.